Mining claim marker: 4-inch PVC pipe Mining claim marker: 4-inch PVC pipe |

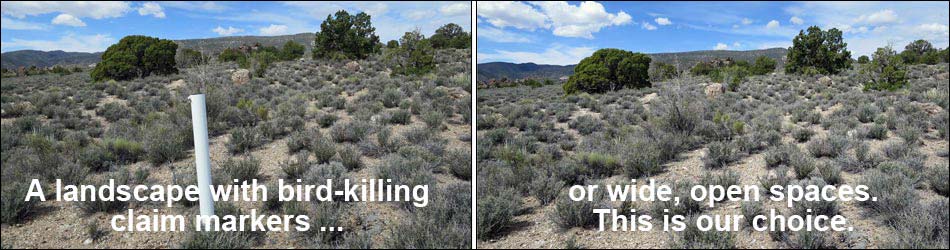

The Problem Nevada has a long history of prospecting and mining. The state was settled by miners just after the end of the American Civil War, and while their efforts brought prosperity and even statehood, in some cases they also left an environmental mess. We are still cleaning up the mess; and the more we do, the more we realize that we need to do even more. While seemingly small and insignificant compared to open pit mines and large-scale prospects that have been abandoned across the state, hollow mining claim markers have turned out to have large negative affects on birds and other small animals. The main problem is that some of our migrating birds nest in cavities (holes in things). In nature, they use old woodpecker nests, rotten holes in old trees, and even cracks in rocky cliffs. In searching for nest cavities, birds like Mountain Bluebirds (mostly in northern Nevada) and Ash-throated Flycatchers (mostly in southern Nevada) hop down into the hollow mining claim markers to investigate -- never to come out again. |

Nevada law empowers citizens to knock down the markers |

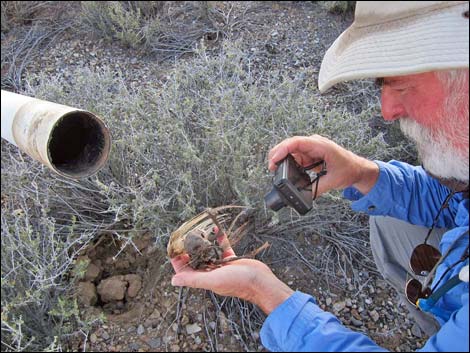

Nobody knows how many birds die every year inside hollow mining claim markers, but estimates are high. Researches have investigated the scope of the problem, and while not every marker contains the remains of birds, many do, and counts are as high as 42 dead birds (I've recently heard of 100!) inside a single mine marker. Even the number of hollow mining claim markers is unknown, but estimates suggest hundreds of thousands across Nevada, and millions across the western United States. Even if only a few markers catch birds each year, the annual number of deaths must be large. Personally, the most I've found is 35 dead birds inside a single marker (mostly Ash-throated Flycatchers), but in addition to birds, I've found dead bats, lizards, mice, chipmunks, scorpions, beetles, tarantula hawk wasps, caterpillars, darkling beetles, and lots and lots of bees, flies, and other insects. Bird species I found dead include Ash-throated Flycatcher, Western Bluebird, Western Screech Owl, House Finch, Northern Mockingbird, Ladder-backed Woodpecker, and Black-tailed Gnatcatcher. In many cases, all that is left is a few old bones. |

Documenting dead bird found inside mining claim marker |

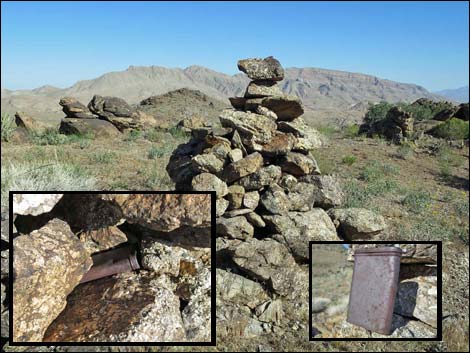

The Law Historically, miners set up large stone cairns (piles of rocks) to mark the corners of their claim, and old mining districts around the state are full of these historic cairns. Claims usually cover about 20 acres in a rectangular strip 1,500 feet long and 600 feet wide. Traditionally, the four corners of the claim, and the midpoint along both long sides, are marked. Thus, each mining claim is identified by 6 markers. Usually, one of the midpoint markers is designated the "discovery post," and to the discovery post is attached a statement about the claim, including how the claim is orientated, when the claim was staked, and who made the claim. If claims are arranged side by side, they can share corner and midpoint markers. |

Dead owl inside a mining claim marker |

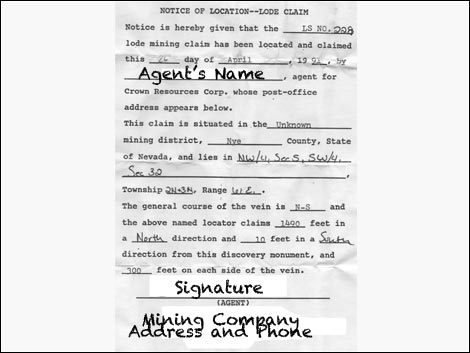

In the "old days," prospectors staked their claims, then filed location information with the state. A filing fee was required, and until about 1990, the fee was $10 per year per claim. The low fee allowed speculators to enter the game, and speculators could establish claims over vast acreages in any area where they thought someone else might want to prospect or where someone else might want to develop. If the speculator got lucky, say a major mining company wanted to move in, they could sell their "worthless" claim for a lot of money. Back in the old days, prospectors marked their claims with stone cairns, but rocks are hard to find in some places, and they are always hard to move, so 4-inch square (4x4) wooden posts became popular. As materials developed, starting in about 1970, prospectors began using 4-inch diameter PVC pipes. Compared to earlier materials, the white pipes were easy to set up, easy to see from long distances, light weight, and long lasting. |

Dead bird and chipmunk |

While 4-inch PVC pipes made life easier for prospectors, they had unintended consequences, and as the evidence mounted, environmental groups such as the Audubon Society raised the alarm about how the markers were trapping and killing many birds. In 2009, the law in Nevada changed to prohibit hollow mining claim markers, required claim owners to retrofit or remove their old markers, and raised the annual fee from $10 to $100 per claim (now $155/yr). Raising the fee was a game changer and essentially put an end to the speculative claims. Claim owners with real claims retrofitted their markers by replacing them with wooden or metal posts, or by simply putting a cap on the original PVC pipe, following current BLM regulations (PDF 1 MB). Over vast swaths of Nevada, and eventually other western states, many speculative claim owners just walked away and abandoned their claims leaving the bird-killing posts upright and scattered across the landscape. |

The law specifies that we leave the marker on the ground |

What Citizens can do in Nevada In Nevada, starting November 1, 2011, the law empowered citizens on federal public lands (not private lands) to knock down mine markers where ever they are found. To make it easier for claim owners to return and retrofit their claims, citizens are required to leave the markers on the ground to mark the spot, although most of the claims are abandoned and it seems silly to leave the 4-inch PVC pipes (now just trash) on the landscape. In Nevada, the BLM and NDOW are working hard to remove hollow mining claim markers, but the numbers are vast and many remain. It is thought that few markers remain in Clark County, and land managers hope to finish cleaning up Clark County during 2016. I am coordinating citizen efforts to knock down markers in southern Nevada. I encourage all users of public lands to knock down hollow mining claim markers, but even more, send me an email and let me know where you found them. I'll get volunteers out for a Mine Marker Take-Down project. |

4-inch PVC pipe and dead birds |

4-inch PVC pipe and dead Ash-throated Flycatcher |

Dead birds |

Dead birds |

Three dead Ash-throated flycatchers |

Dead Ash-throated Flycatchers |

At least two dead Ash-throated flycatchers |

Dead Ash-throated flycatcher |

Dead sparrow |

Dead House Finch |

More than one dead Ash-throated flycatcher |

Two dead birds (one Ash-throated flycatcher) |

Dead Western Screech Owl |

Dead Ash-throated Flycatcher |

Dead Black-tailed Gnatcatcher and chipmunk |

Two live and one dead Side-blotched Lizards |

Dead Western Pipistrelle Bat |

Dead bad |

Dead Tenebrionid beetles and Giant Desert Hairy Scorpion |

Dead bird, Tarantula Hawk wasps, and beetles |

Historic stone cairn with claim papers inside cigar can Historic stone cairn with claim papers inside cigar can |

Historic stone cairn with 4x4 wooden post |

|

|

4-inch, non-perforated PVC pipe with a cap -- this is legal |

4-inch non-perforated PVC pipe with a cap -- this is legal |

4-inch PVC pipe with a stone cap -- this does not make it legal |

Notice of Location claim paper |

Note: All distances, elevations, and other facts are approximate.

![]() ; Last updated 191212

; Last updated 191212

| Postcards | Copyright, Conditions, Disclaimer | Home |